SUMMARY

The Climate Change Authority (the Authority) is an independent body charged with providing advice to the Commonwealth Government on climate change policy. As part of this remit, the Caps and Targets Review will address two broad topics:

- Australia’s progress towards its medium and long term emissions reduction targets; and

- Australia’s appropriate emissions reduction goals.

This is the Authority’s first review of Australia’s emissions reduction goals and, as in the case of its recent review of Australia’s Renewable Energy Target, it seeks input and feedback from interested parties. This Issues Paper outlines the Authority’s proposed approach to the Review, and identifies what it sees as the main issues. The Authority would welcome comments on both its proposed approach and the issues it has identified (and any it may have overlooked).

As its starting point, the Authority accepts the view that it is in Australia’s interests to support global emissions reductions to limit global average warming to 2 degrees Celsius or less. Additional starting points are Australia’s long term target to reduce emissions to 80 per cent below 2000 levels by 2050, and the policy action of Australian governments at all levels to reduce emissions. The 2050 target and policy measures (which include the carbon price) are among the ‘givens’ for this Review.

The Authority is required to report to the Government by 28 February 2014. Its report will include recommendations on a national emissions reduction target for 2020, and caps (that is, limits on emissions) for the first five years of trading under the carbon pricing mechanism.

The Authority proposes to focus on four main issues in recommending emissions reduction goals for Australia:

- the science-related aspects of global emissions budgets, pointing to the overall level of emissions reductions required to limit warming to 2 degrees;

- approaches to sharing global emissions budgets among nations;

- the extent and nature of international action to reduce emissions; and

- the economic and social implications of different emissions reduction goals for Australia.

Given the long term nature of climate change, and of the policy frameworks for dealing with such change, the Authority will need to conduct its analysis and determine its recommendations in the context of timeframes that extend well beyond 2020. Those longer term perspectives could well have implications for the recommendations for 2020. The Authority will assess Australia’s possible actions beyond 2020, and will consider making additional recommendations on budgets, trajectories and/or targets for longer periods; for example, out to 2030 or 2050.

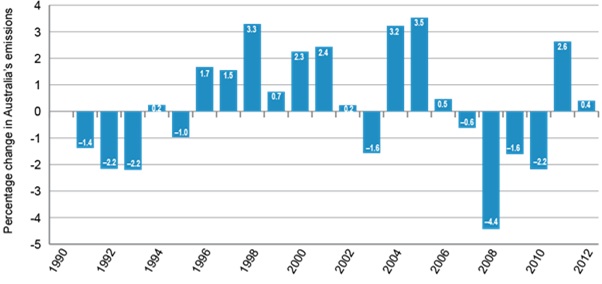

In its report, the Authority will also review trends in Australia’s emissions during the past two decades, and examine the main factors contributing to those trends and their implications for Australia’s medium and long term targets.

Submissions relevant to the various issues to be covered in the Authority’s Review should be lodged by 30 May 2013. The Authority proposes to release its draft report in October, and to provide opportunities for public comment on its draft findings and recommendations before finalising its views. The Authority is required to present its final report to the Commonwealth Government in February 2014.

Chapter 1. Introduction

Australia is taking action to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions and build a low-emissions economy. This action contributes to global efforts to reduce the risks of dangerous climate change and helps to secure our future prosperity. Through the Caps and Targets Review, the Climate Change Authority (the Authority) will assess Australia’s progress toward its medium and long term emissions reduction targets, and examine appropriate next steps to reduce emissions.

This chapter introduces the Caps and Targets Review. It sets out what the Authority needs to do and how it plans to approach its task. Chapter 2 discusses the broader setting, including the causes and impacts of climate change, Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, and the policies and programs in place to reduce those emissions. These issues define the broad context within which the Review will operate, but are not themselves subjects of this Review.

Subsequent chapters outline the main issues that will be addressed in the Authority’s findings and recommendations. Chapter 3 and Chapter 4 focus on the considerations most relevant to Australia’s national carbon budget, indicative national trajectory, 2020 target, and choices to be made in setting caps (Box 1 defines these key terms). Chapter 5 reviews past progress in reducing emissions, and the evaluation framework required to assess future progress towards Australia’s medium and long term targets.

Public consultation is central to all of the Authority’s work. This Issues Paper seeks input from interested parties on the Authority’s proposed approach to the Review and the issues it proposes to consider, to better inform its analysis and recommendations. Key issues are summarised in Chapter 6.

1.1. The Review task

The Caps and Targets Review will examine Australia’s goals to reduce emissions and its progress. In its report to the Commonwealth Government, the Authority plans to:

- review progress towards achieving Australia’s medium and long term emissions reduction targets;

- recommend a national carbon budget and indicative national emissions trajectory for Australia, which may extend beyond 2020;

- recommend a 2020 emissions reduction target, and caps for the first five trading years of the carbon pricing mechanism, as further steps towards Australia meeting its longer term goals; and

- consider how Australia might meet its trajectory, budget, target and caps, including how different sectors contribute to emissions reductions, and the role of international emissions trading.

- The Authority is required to report its findings and recommendations to the Commonwealth Government by 28 February 2014.

Box 1 Key terms

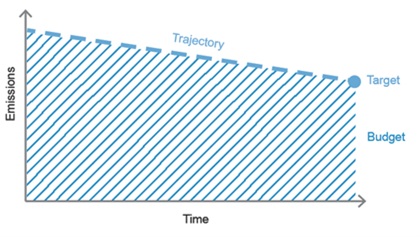

Target: Goal for national emissions; usually expressed in terms of a specific year. The Authority will recommend a 2020 target and, possibly, target(s) for later years (the timeframe is discussed in Section 3.1.1). Australia’s target relates to ‘net’ emissions – that is, emissions in Australia, adjusted for any import and export of emissions units.

Trajectory: Australia’s year-by-year pathway to its target. The trajectory provides the starting point for calculating annual caps. The Authority will recommend a trajectory from 2013 to 2020, and possibly beyond (discussed in Section 3.1.1).

Budget: Australia’s cumulative emissions allowance over a period of time. The Authority will recommend a budget from 2013 to 2020, and possibly beyond.

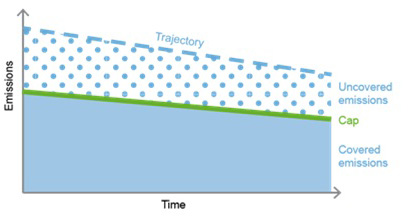

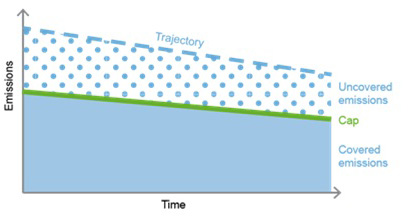

Cap: The year-by-year limit on emissions from sources covered by the carbon pricing mechanism (‘covered emissions’). The gap between the trajectory and cap allows for emissions from sources outside the carbon pricing mechanism (‘uncovered emissions’). The Authority will recommend five years of caps, from 2015–16 to 2019–20.

Source: Climate Change Authority

This is the Authority’s first review of Australia’s emissions reduction goals and progress. It spans two of the Authority’s primary responsibilities under the Clean Energy Act 2011 (Cth): the periodic review of carbon pollution caps (s 289); and the annual review of progress (s 291). These two issues are interconnected: Australia’s progress towards its medium and long term targets is a relevant consideration in deciding what Australia’s target, trajectory, budget and caps should be; and Australia’s 2020 target and budget are key benchmarks for developing indicators and milestones to track Australia’s progress. The Authority therefore proposes to deal with both topics in this Review.

As an independent statutory body, the Authority’s work is guided by the principles set out in the Clean Energy Act 2011 and the Climate Change Authority Act 2011 (Cth). These include that measures to respond to climate change should:

- be economically efficient, environmentally effective, equitable and in the public interest;

- support the development of an effective global response to climate change, and be consistent with Australia’s foreign policy and trade objectives; and

- take account of the impact on households, businesses, workers and communities.

The Clean Energy Act 2011 also sets out specific factors the Authority must consider. These form the basis of the discussion in Chapters 3, 4 and 5.

1.2. Approach to the Review

Climate change is a global problem. Australia’s emissions reduction goals and actions are part of the broader context of global action, which in turn is guided by the common global objective to avoid dangerous climate change. Extensive analysis of the risks and impacts of climate change have led to the broad global agreement that this objective requires that global warming (that is, the increase in global average temperature from pre-industrial levels) should be limited to no more than 2 degrees Celsius.

Climate change poses serious risks to Australia’s environment, economy and society; these are discussed briefly in Section 2.1. Successive governments at all levels have taken action to reduce Australia’s emissions, giving practical effect to Australia’s commitment to play its part in global action. The objectives of the Clean Energy Act 2011 and Australia’s international commitments recognise Australia’s overarching interest in limiting warming to 2 degrees. The Authority accepts this view as a given in approaching this Review.

The Authority does not intend to re-examine the fundamental costs and benefits of global action to reduce emissions in the Caps and Targets Review. These have been comprehensively examined in previous work; most relevantly by Professor Garnaut in his 2008 climate change review and his 2011 update. Professor Garnaut concluded that the costs of strong action to reduce emissions are outweighed by the benefits of lower climate change impacts and risks – that is, the costs of action are less than the costs of inaction (Garnaut, 2008, Ch 11). The Government accepted this finding, introducing new policies and measures, including the carbon pricing mechanism (see Box 2), to strengthen Australia’s emissions reduction efforts.

Box 2 Carbon pricing mechanism

The carbon pricing mechanism began on 1 July 2012. It applies to more than 350 of Australia’s biggest emitters. These ‘liable entities’ have to report on, and pay a price for, their greenhouse gas emissions; they therefore have an incentive to reduce emissions.

The carbon price is fixed each year for the first three years, starting at $23 a tonne in 2012–13 and growing at 2.5 per cent in real terms each year.

From 2015–16, the carbon pricing mechanism sets a cap for emissions covered by the scheme and the price will be determined in the market place. Through this Review, the Authority will recommend five years of caps; the Government then sets the caps through regulations under the Clean Energy Act 2011. In the event that regulations are not made, or are disallowed, the Act sets out default caps, which will apply every year until regulations are made.

Liable entities will be able to buy Australian units and also have access to international carbon markets. The carbon pricing mechanism will be linked to the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS) – initially with a one-way link from 2015 (allowing liable entities under the carbon pricing mechanism to import carbon allowances from the EU ETS) and with reciprocal trading from 2018.

Between 2015 and 2020, liable entities will be able to meet up to 50 per cent of their annual liability with eligible units from the EU ETS and the Kyoto Protocol. Only 12.5 per cent of liabilities will be able to be met through Kyoto units.

Source: Climate Change Authority, based on the Clean Energy Act 2011

1.2.1. Australia’s emissions reduction goals

The Authority will review Australia’s progress and make recommendations for Australia’s emissions reduction goals, in light of our national interest to limit global warming to 2 degrees or less.

The Authority cannot apply a simple formula to derive targets and caps; many considerations are relevant to determining Australia’s appropriate emissions reduction goals. In addition to general guiding principles, the Clean Energy Act 2011 (s 289) sets out a number of specific factors to which the Authority must have regard:

- Australia’s international obligations and undertakings to reduce greenhouse gas emissions;

- Australia’s medium and long term targets for reducing emissions;

- progress towards emissions reductions;

- global action to reduce emissions;

- estimates of the global emissions budget;

- the economic and social implications associated with various levels of emissions caps;

- voluntary action to reduce Australia’s emissions;

- estimates of emissions that are not covered by the Clean Energy Act 2011(uncovered emissions);

- estimates of the number of Australian carbon credit units that are likely to be issued;

- the extent (if any) of non-compliance with the Clean Energy Act 2011 and associated provisions;

- the extent (if any) to which liable entities have failed to surrender sufficient units to avoid liability for unit shortfall charge;

- Commonwealth acquisitions, or proposed acquisitions, of eligible international emissions units; and

- such other matters (if any) as the Authority considers relevant.

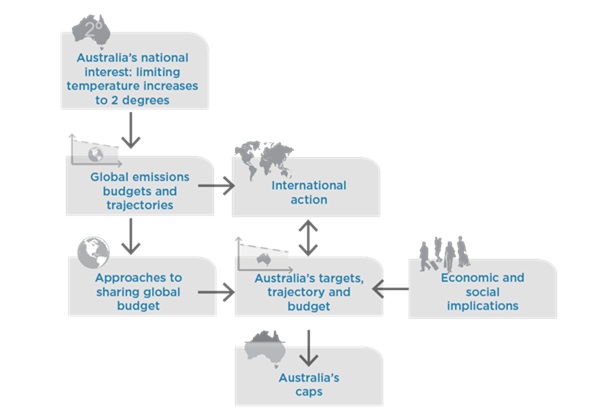

For the purposes of this Review, the Authority has grouped these matters into four themes: the science-related aspects of global emissions budgets; the extent and nature of international action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; approaches to sharing global emissions budgets among nations; and the economic and social implications of different goals. The Authority will seek to synthesise its analysis across these four themes in framing recommendations on Australia’s next steps towards its long term target.

Some of the more technical factors, such as the extent of any non-compliance and liability for the unit shortfall charge, will become more relevant once the trading phase of the carbon pricing mechanism commences, and may have a greater influence on cap setting in the future.

The Authority’s approach to assessing Australia’s appropriate emissions reduction goals is illustrated in Figure 1. Australia’s national interest in limiting temperature increases to 2 degrees corresponds to global emissions budgets consistent with this aim. Approaches to determining Australia’s fair and defensible share of these budgets, along with the economic and social impacts, and the extent of other countries’ actions, also provide guidance. The two-way arrow between international action and Australia’s action illustrates the possibility that Australia’s climate policy will influence others. Once the overall goals have been determined, consistent recommendations on caps for the carbon pricing mechanism can be considered.

Figure 1 Australia’s emissions reduction goals: key considerations

Source: Climate Change Authority

1.2.2. Australia’s progress

The Authority is required to review progress in achieving Australia’s medium and long term emissions reduction targets. The Authority is not required to make specific recommendations on progress, but will report on its findings and may make recommendations if its analysis suggests any specific actions are warranted. The Clean Energy Act 2011 (s 291) requires that the Authority have regard to:

- the level of greenhouse gas emissions in Australia;

- the level of purchases of eligible international emissions units (whether by the Government or others);

- the level of uncovered emissions;

- voluntary action to reduce emissions; and

- such other matters (if any) as the Authority considers relevant.

The Authority will review both progress made since 1990, and issues related to future emissions, in this Review (see Chapter 5).

1.2.3. Uncertainty and risk

Any policy process that sets goals for the future, or evaluates progress against future goals, needs to deal with uncertainty. This Review is no exception. Nobody (including the Authority) can be sure how estimates of the global emissions budget, the impacts associated with a given temperature increase, the scale and pace of overall global action to reduce emissions, and Australia’s mitigation opportunities and costs will unfold. As new information emerges, views on the required global action and Australia’s appropriate contribution are likely to change. The Authority has to make its judgements based on the information available at the time, but also taking account of the risks that those judgements could prove to be wide of the mark.

Australia’s policy framework helps deal with this uncertainty and manage the associated risks. Under the Clean Energy Act 2011, the Government will set five years of binding emissions caps in 2014 for the period to 2019-20. Subsequent caps will be added later. This helps to reduce risks to investors by providing some guidance on Australia’s future policy, while retaining flexibility to respond to new information. Similarly, the linking of the carbon pricing mechanism to international carbon markets (and the price ceiling for the first three years of the flexible price period) helps to reduce the risks of more severe impacts in the event that Australia’s mitigation opportunities prove to be more limited or costly than anticipated.

The Authority, in framing its recommendations on targets, trajectories, budgets and caps, will have regard to the need to reduce uncertainty and manage risks.

Chapter 2. Context and scope

The Authority will conduct a broad inquiry to evaluate Australia’s progress and inform its recommendations on Australia’s emissions reduction goals. This Section briefly summarises two foundational issues – climate science and Australia’s action on climate change – which provide the starting point for the Review, and define the scope of the Authority’s current task. Implications for the scope of the Review are summarised in Box 4 at the end.

2.1. Climate science

An understanding of the most recent climate science provides important context for the Authority’s analysis, and anchors the Review to Australia’s national interest in limiting warming to no more than 2 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

There is unequivocal scientific evidence that the global climate system is warming, and it is very likely that most of the observed warming during the past 50 years was due to increased greenhouse gas emissions resulting from human activity (IPCC, 2007, p 10). The bulk of these emissions were derived from world demand for energy. The largest and fastest-growing contributor to global warming is carbon dioxide (CO2), emitted when fossil fuels are burnt to meet those energy demands. Other greenhouse gas emissions are growing as well, including methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O).

The level of global warming depends on cumulative emissions over time. Greenhouse gases trap radiant energy from the sun in the lower atmosphere, causing global warming and resulting in changes to the climate system. Higher emissions lead to higher concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, trapping more radiant energy and leading to greater increases in global average temperature.

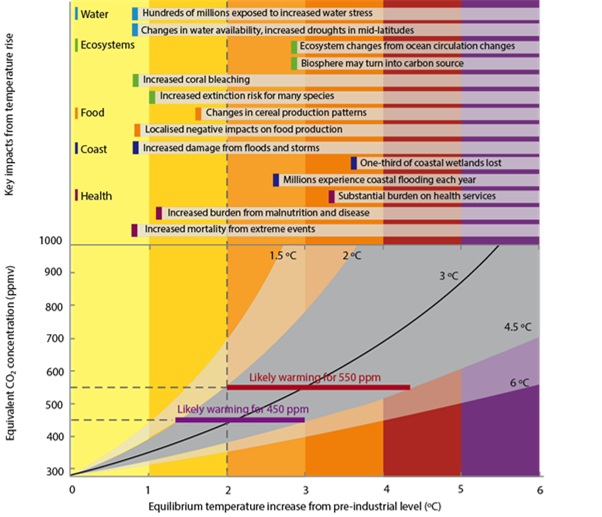

The precise relationship between concentration and temperature increase is uncertain, and can only be described in terms of probability. Figure 2 illustrates this relationship for a range of concentration levels. For example, deep and rapid cuts in global emissions could allow the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere to stabilise at 450 parts per million carbon dioxide equivalent (ppm CO2-e). This corresponds to a roughly even (50 per cent) chance of limiting warming to 2 degrees, and a likely warming of between 1.5 and 3 degrees. Slower global emissions reductions could allow the concentration to stabilise at 550 ppm CO2-e, with a roughly even chance of limiting warming to 3 degrees, and likely warming of between 2 and 4.5 degrees.

Figure 2 Relationship between greenhouse gas atmospheric concentration, temperature and global impacts

Source: Adapted from Knutti and Hegerl, 2008

Strong growth in global emissions during the past few decades has increased the risk of dangerous climate change and, with it, the cost of adapting to a warmer world. Global average surface temperatures during the past decade were the warmest on record, around 0.8 degrees above pre-industrial levels (Jones et al, 2012, p 1). Even if emissions were to drop immediately to zero, the world would continue to warm at least a further 0.6 degrees, owing to inertia in the climate system (European Commission, 2009, p 1).

Global emissions are tracking towards the upper bounds of global projections and, without strong global action to reduce emissions, are on a pathway consistent with a 4 degree increase in global average temperature by 2100 (World Bank, 2012, p xiii). As indicated in Figure 2, temperature rises beyond 2 degrees bring risks of severe impacts of climate change, from widespread loss of corals and other organisms that play a crucial part in the oceanic food chain, to extensive loss of terrestrial life.

The impacts of climate change will escalate rapidly as more emissions accumulate. A global average temperature rise of 4 degrees from pre-industrial levels is well outside the relatively stable temperatures of the past 10 000 years, which have provided the environmental context for the development of human civilisation. A temperature increase of 4 degrees above pre-industrial levels would give an 85 per cent probability of initiating large-scale melting of the Greenland icesheet, put half of the world’s species at risk of extinction and place 90 per cent of coral reefs above critical limits for bleaching (Garnaut, 2011, pp 100–101).

Australia, as the driest inhabited continent in the world, faces more serious impacts than most other developed countries. Even if global average warming is limited to 2 degrees, Australia faces substantial changes in the distribution of rainfall, the frequency and intensity of flood and drought, the intensity of cyclones, and the intensity and frequency of conditions for severe bushfires (Garnaut, 2011, p 100).

More than 85 per cent of the population of Australia lives in coastal regions (CSIRO, 2011, p 50). Further development and population growth on the coast will exacerbate the risk of adverse impacts from sea level rise. Significant losses of unique Australian animal and plant species are expected to occur in important sites, such as the Great Barrier Reef (CSIRO, 2011, p 45).

The impacts of climate change are becoming more evident. Australia has experienced a number of more intense weather events, including extreme heat across Australia, very heavy rainfall on the east coast, and a long-term drying trend affecting the southwest corner of Western Australia (Climate Commission, 2013, p 4). Australia’s 2012–13 summer was also the hottest on record, with the most consecutive days with an average national daily maximum temperature of more than 39 degrees (Climate Commission, 2013, p 20).

Climate science is increasingly highlighting the need for urgent, decisive and coordinated global action to reduce emissions if there is to be any real prospect of limiting global temperature increases to 2 degrees.

2.2. Australia’s action on climate change

Successive governments at all levels have taken action to reduce Australia’s emissions for more than two decades, giving practical effect to Australia’s commitment to play its part in global action. The Authority’s recommendations on emissions reduction goals will inform the next steps in this process.

This Section briefly outlines Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, mitigation policies, future goals for reducing emissions and commitments under international agreements, and discusses their relevance to this Review.

2.2.1. Australia’s emissions

Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions are high in per capita terms compared with other countries (discussed further in Section 3.2.2). This reflects a range of factors, including that fossil fuels dominate Australia’s energy supply, and that energy-intensive industries comprise a relatively large share of the economy. Australia emitted around 578 million tonnes (Mt) CO2-e in 2012, an increase of around 5 per cent compared with 1990 (Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, 2012a).

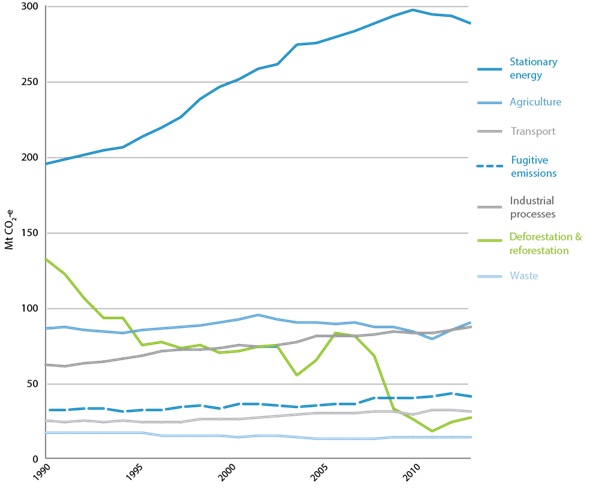

Stationary energy accounts for around one-half of Australia’s emissions; it has grown from 195 Mt CO2-e in 1990 to 288 Mt in 2012 (Figure 3). Agriculture and transport each accounted for 16 per cent and 15 per cent of national emissions, respectively, in 2012 (Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, 2012a).

Figure 3 Australia’s emissions, 1990–2012

Mt CO2-e = megatonne CO2 equivalent

Note: Year refers to emissions in the financial year ending June.

Source: Climate Change Authority, based on Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, 2012a

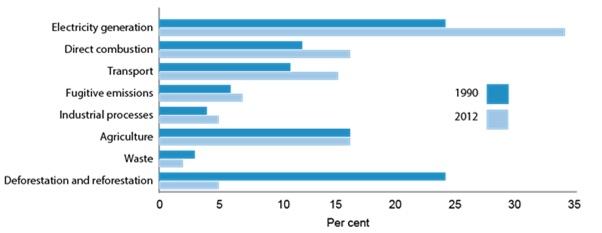

The sectoral mix of Australia’s emissions has changed significantly since 1990. Emissions from electricity generation and other stationary sources have grown strongly; their share of national emissions has grown from 36 per cent in 1990 to around 50 per cent in 2012. In contrast, net emissions from deforestation and reforestation have fallen dramatically; their share has declined from 24 per cent to around 5 per cent (Figure 4) (Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, 2012a).

In reviewing Australia’s progress, the Authority will examine the underlying drivers of these changes in Australia’s emissions, and the contribution of different policy measures over time. This is discussed further in Chapter 5.

Figure 4 Sectoral contributions to Australia’s emissions, 1990 and 2012

Note: Year refers to emissions in the financial year ending June.

Source: Climate Change Authority, based on Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, 2012a

2.2.2. Policies and measures

Governments at all levels have used a wide variety of policies and measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (and, often at the same time, to pursue broader environmental and economic goals). These include regulatory controls on land clearing, energy efficiency standards for appliances and buildings, market-based incentives for renewable energy deployment, and grants and other funding to support research and development of new low-emissions technologies.

The most recent significant policy development is the Commonwealth Government’s Clean Energy Future Plan. Announced in 2011, the Plan has four elements: a carbon price (discussed in Box 2, Chapter 1), renewable energy, energy efficiency and action on the land. The Plan also details how the Government will support Australian households, businesses and communities to transition to a clean energy future.

The Authority will examine the costs and benefits of its recommended goals in light of Australia’s existing policy landscape. This broad policy portfolio, including the carbon pricing mechanism and complementary measures in covered and uncovered sectors, will have contributions to make to the achievement of Australia’s goal. The Authority does not intend to examine the merits of the carbon pricing mechanism, nor its detailed design, in this Review.

Existing policy settings have a major influence on the impacts of different goals. The coverage of the carbon pricing mechanism determines which emission sources sit within the cap, and which emission sources fall outside the scheme. Linkage of Australia’s scheme to international carbon markets strongly affects the carbon price covered sources will face. Other policies influence trends in emissions from uncovered sources. The Authority will consider the combined effect of all measures in determining the outlook for emissions reductions within Australia, and the extent to which international units may be used to meet the recommended national trajectory and budget.

Through this Review, the Authority may identify opportunities to improve the existing policy portfolio, and areas where gaps or weaknesses hinder Australia’s progress. These findings could provide the basis for more detailed reviews in the future, including the Authority’s scheduled review of the carbon pricing mechanism in 2016.

2.2.3. Emissions reduction targets

The Authority will take account of Australia’s medium and long term targets, as well as Australia’s international obligations and undertakings in this Review. Of most relevance are:

- Australia’s undertaking under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) to reduce emissions by 5 per cent, up to 15 per cent, or 25 per cent from 2000 levels by 2020. Further detail on the Government’s 2020 target policy is summarised in Box 3.

- Australia’s undertaking under the Kyoto Protocol to limit average annual emissions in the period 2013–2020 to 99.5 per cent of 1990 levels. This limit was calculated based on the Government’s unconditional 5 per cent target.

- The Government’s target to reduce emissions by 80 per cent from 2000 levels by 2050, reflected in the objectives of the Clean Energy Act 2011.

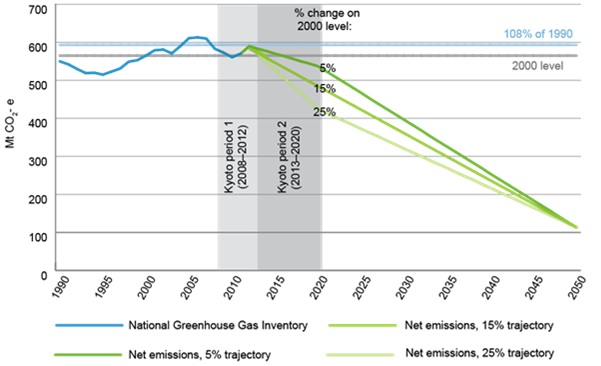

These targets are illustrated in Figure 5, in the context of emissions since 1990. The Government’s stated 2020 target conditions are set out in Box 3.

Australia also has commitments under the UNFCCC to help developing countries mitigate and adapt to climate change, and specific obligations to measure, report and verify its emissions.

Figure 5 Australia’s emissions since 1990, and outlook to 2050

Note: Trajectories to the 2020 and 2050 targets are illustrative; they begin in 2012 and assume a straight line reduction to the target. The Authority will recommend a trajectory as part of its final report.

Source: Climate Change Authority, based on Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, 2012b

Box 3 Commonwealth Government’s 2020 target policy

Reduce emissions by 5 per cent on 2000 levels

Conditions: None

Reduce emissions beyond 5 per cent

Conditions: The Government will not increase Australia’s emissions reduction target above 5 per cent until:

- the level of global ambition becomes sufficiently clear, including both the specific targets of advanced economies, and the verifiable emissions reduction actions of China and India;

- the credibility of those commitments and actions is established, for example, by way of a robust global agreement or commitments to verifiable domestic action on the part of the major emitters including the United States, India and China; and

- there is clarity on the assumptions for emissions accounting and access to markets.

Reduce emissions by 15 per cent on 2000 levels

Conditions: International agreement where major developing economies commit to restrain emissions substantially and advanced economies take on commitments comparable to Australia’s. In practice, this implies:

- Global action on track to stabilisation between 510 and 540 ppm CO2-e.

- Advanced economy reductions in aggregate in the range of 15–25 per cent below 1990 levels.

- Substantive measurable, reportable and verifiable commitments and actions by major developing economies, in the context of a strong international financing and technology cooperation framework, but which may not deliver significant emissions reduction until after 2020.

- Progress towards inclusion of forests (reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) and the land sector, deeper and broader carbon markets, and low carbon development pathways.

Reduce emissions by 25 per cent on 2000 levels (up to 5 percentage points through Government purchase)

Conditions: Comprehensive global action capable of stabilising CO2-e concentrations at 450 ppm CO2-e or lower. This requires a clear pathway to achieving an early global peak in total emissions, with major developing economies slowing the growth and then reducing their emissions, advanced economies taking on reductions and commitments comparable to Australia, and access to the full range of international abatement opportunities through a broad and functioning international market in carbon credits. This would involve:

- Comprehensive coverage of gases, sources and sectors with inclusion of forests (reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation) and the land sector (including soil carbon initiatives (for example, biochar) if scientifically demonstrated) in the agreement.

- Clear global trajectory, where the sum of all economies’ commitments is consistent with 450 ppm CO2-e or lower, and with a nominated early deadline year for peak global emissions not later than 2020.

- Advanced economy reductions, in aggregate, of at least 25 per cent below 1990 levels by 2020.

- Major developing economy commitments to slow growth and to then reduce their absolute level of emissions over time, with a collective reduction of at least 20 per cent below business as usual by 2020 and a nomination of peaking year for individual major developing economies; global action which mobilises greater financial resources, including from major developing economies, and results in fully functional global carbon markets.

Note: ‘Advanced economies’ refers to Annex I Parties to the UNFCCC and at least some other high–middle income economies; ‘major developing economies’ refers to non-Annex I members of the Major Economies Forum.

Source: Commonwealth Government, 2009; Wong, 2010

Australia’s international undertaking to reduce its emissions by at least 5 per cent from 2000 levels by 2020, and limit average annual emissions to no more than 99.5 per cent of 1990 levels during 2013–2020, has been expressed as a minimum. The Government has not ruled out the option of moving up the target range, and noted the Authority’s role in this context (Combet, 2012).

The Government’s existing UNFCCC and Kyoto Protocol commitments affect the scope of this Review. The Authority views the 2020 target and 2013–2020 budgets as minimums and will not recommend caps for the carbon pricing mechanism that would result in Australia not meeting either of these commitments.

The Authority will consider whether a 5 per cent target is the appropriate 2020 target for Australia, or whether a more stringent target is in Australia’s national interest. The Authority is required to take account of the specific conditions associated with Australia’s target range, but its role is not limited to interpreting those conditions. In assessing Australia’s appropriate emissions reduction goals, the Authority is required to consider the broader list of considerations mentioned in Section 1.2.1.

Australia’s longer term outlook for emissions reductions is an important consideration in reviewing goals and progress. The Government’s target to reduce emissions by 80 per cent from 2000 levels by 2050 therefore provides an important reference point for this Review, and the Authority proposes to take that reference point as a given.

Box 4 Review context and scope: key points

- The Review will consider the appropriate level of Australia’s emissions reduction goals, not whether Australia should take action at all.

- The Authority will recommend goals and evaluate progress in light of the existing policy landscape.

- Australia’s unconditional 5 per cent reduction target for 2020 is the minimum level the Authority will consider.

- The Authority will have regard to, but is not constrained by, the Government’s stated conditions for the 2020 target.

- Australia’s 80 per cent reduction target for 2050 is an important consideration in determining Australia’s goals, and a key benchmark for tracking progress.

Chapter 3. Australia’s emissions reduction goals

This chapter sets out the issues relevant to recommending targets, trajectories and budgets for Australia. It begins with the timeframes and accounting arrangements used to define targets, trajectories and budgets. It then discusses the four broad themes identified in Chapter 1: global emissions budgets, international action, approaches to sharing global budgets, and economic and social implications. Because emissions caps take the national goals as a starting point and have several additional considerations, they are discussed separately in Chapter 4.

3.1. Defining targets, trajectories and budgets

To make recommendations on targets, trajectories and budgets, the Authority must first answer two important questions. The first is the timeframes over which the Authority will recommend targets, trajectories and budgets. The second is the scope (for example, the scope of emissions sources and sinks) of the recommended targets, trajectories and budgets.

3.1.1. Timeframes

The Authority is required to make recommendations on national carbon budgets and indicative national trajectories. The Authority will make recommendations applying to 2013–2020, to align with its recommendations on emissions caps and with the second commitment period under the Kyoto Protocol. Australia’s action to 2020 represents its next step towards its long term target to reduce emissions to 80 per cent below 2000 levels by 2050. The Authority will assess Australia’s possible actions beyond 2020, and will consider making additional recommendations on budgets, trajectories and/or targets for longer periods; for example, out to 2030 or 2050.

Providing specific guidance on the scale and pace of Australia’s emission reductions beyond 2020 has benefits. It links Australia’s action more directly to the scientific basis for action, reduces uncertainty for investors in long-lived assets (such as electricity generators and industrial plants) and could inform Australia’s contribution to international negotiations for post-2020 action, which are scheduled to conclude in 2015. It also provides an early indication of future recommendations on caps for the carbon pricing mechanism. Any such longer term recommendations would, of course, be subject to review and revision in light of new information.

Potential recommendations for emissions reduction goals beyond 2020 might include:

- an indicative national trajectory to 2030 or 2050. This would implicitly also define a long term national carbon budget;

- a national carbon budget to 2030 or 2050, which would retain flexibility on the long term trajectory;

- medium term carbon budgets for periods after 2020 (as recommended by the United Kingdom’s Committee on Climate Change); and/or

- a target for 2025 or 2030.

The Authority could also consider recommending ranges for any of these variables. The Authority welcomes comments and analysis on the relative merits of these and other options.

3.1.2. Accounting

In setting targets, trajectories and budgets, it is necessary to specify which emissions count towards a target. These are generally a subset of overall emissions. For example, the Kyoto Protocol accounting rules provide detailed guidance regarding which greenhouse gases, sectors and sources count towards national targets under the Protocol, and which are excluded (UNFCCC Secretariat, 2008). Australia’s Kyoto target therefore excludes emissions of some greenhouse gases, and excludes emissions from international aviation and shipping. Australia can only count official Kyoto emission units towards its Kyoto target; it cannot count units generated under other regulatory schemes (such as California’s emissions units).

As discussed in Section 2.2.3, Australia has committed to a minimum target for 2013–2020 under the Kyoto Protocol. The Authority will therefore recommend a target, trajectory and budget to 2020 that are consistent with the Kyoto Protocol accounting rules.

Australia could adopt additional emissions reduction goals that go beyond its Kyoto commitment. For example, Australia could set a target or budget that includes emissions from international shipping and aviation, or it could count a wider range of international emission units (for example, allowances from the United States). The Authority welcomes views on whether, and to what extent, such a target is warranted.

One specific Kyoto accounting issue requires particular attention in this Review. Where a country’s emissions are lower than its Kyoto target, the accounting rules allow it to ‘carry over’ the extra emission units to the next commitment period. Australia has come in under its target in the

2008–2012 period; emissions are estimated to average 105 per cent of 1990 levels, below its 108 per cent target.

The Authority will consider whether and how the carry over should be considered in determining Australia’s emissions reduction goals. Options include:

- voluntarily cancelling the extra units (essentially, strengthening Australia’s first commitment period target from 108 to 105);

- using the extra units to expand the cap;

- taking it into account in determining Australia’s 2020 goals (for example, using it to set a more ambitious target and budget); or

- holding the extra units as insurance to help ensure Australia meets its second Kyoto target (for example, using it to manage the risk that uncovered emissions may be higher than expected, as discussed in Chapter 4).

The Authority will examine the factors contributing to Australia’s performance in the first commitment period, and welcomes comments on how the carry over should be used.

3.2. Key considerations

As indicated in Chapter 1, the Authority cannot use a simple formula to derive its recommendations for Australia’s emissions reduction goals. It must consider the evidence, and associated uncertainty and risk, to form its judgement. The four broad issues mentioned earlier – the science-related aspects of global emissions budgets; the extent and nature of international action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions; approaches to sharing global emissions budgets between nations; and the economic and social implications of different goals – are discussed in this section. The Authority would welcome input on each of these issues.

3.2.1. Global emissions budgets

A global emissions budget is a level of cumulative emissions to give the world a certain probability of remaining within a chosen temperature limit. For any given global temperature goal, the associated budget illustrates how much of the world’s emissions quota has been used and how much remains. In turn, this informs future actions; the more of the quota that is spent now, the less remains for future use.

A global emissions budget highlights the overall constraint within which national budgets and targets must cumulatively remain if the temperature goal is to be achieved. Section 3.2.3 discusses different approaches to sharing global budgets among nations.

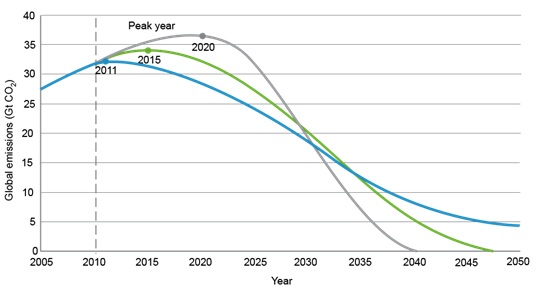

For any given budget there is any number of possible emission trajectories. Figure 6 illustrates three different global emissions trajectories: each has a different peaking year, but each is consistent with the same global emissions budget. The later emissions peak, the faster emissions need to be reduced in the future. If more rapid reductions require abrupt and disruptive economic and social change, there may be a limit to the set of feasible trajectories.

Figure 6 Illustrative alternate global emissions trajectories for a given global emissions budget

Gt CO2 = Gigatonne CO2

Note: The budget depicted is 750 Gt of CO2.

Source: Adapted from German Advisory Council on Global Change, 2009

The relationship between global emissions budgets and temperature outcomes is complex and there are a number of sources of uncertainty. As a result, the temperature change associated with a specified budget is described in probabilistic terms. Table 1 sets out budgets for cumulative CO2 emissions from 2010 onwards. It shows how the probability of limiting global warming to 2 degrees declines as the budget increases. Moving from a required probability of 50 per cent to 80 per cent reduces the available budget by more than two-thirds. Global CO2 emissions were roughly 36 gigatonnes (Gt) in 2010; the budget associated with an 80 per cent chance represents only 14 more years of emissions at that level (beyond 2010), after which emissions would need to fall to zero and remain there indefinitely (Raupach et al, 2011, pp 4, 31).

Table 1 Likelihood of limiting warming to 2 degrees under different global emissions budgets

|

Probability of remaining within 2 degree limit |

Global budget from 2010 onwards (Gt CO2) |

Years of emissions at 2010 levels |

|---|---|---|

|

Gt = gigatonne CO2 |

||

|

80% |

485 |

14 |

|

67% |

993 |

28 |

|

50% |

1679 |

47 |

Accounting issues arise in defining global emissions budgets, just as they do in defining Australia’s target. Budgets can be defined for CO2 only, or for all greenhouse gases. There are some technical challenges associated with defining multigas budgets, as gases behave differently in the atmosphere and contribute to long term temperature change in different ways.

The Authority will need to consider which global emissions budget is most relevant to determining Australia’s emissions reduction goals, and welcomes views and analysis on this matter.

3.2.2. International action

Given the global nature of climate change and economic activity, the international context is important when considering an appropriate 2020 target for Australia. There are three relevant dimensions:

- the overall level of global action, to understand how the world is tracking towards a climate change solution, and how it compares to the conditions associated with the Government’s target range;

- how different 2020 Australian targets (including the Government’s target range) compare to the 2020 targets of other major emitting economies; and

- the ability of Australian action to influence other countries and catalyse greater global action.

The international context is also relevant to how Australia’s economy will change over time, and can affect the competitiveness of Australian industry. The carbon pricing mechanism addresses competitiveness concerns through a number of industry assistance mechanisms, and the Productivity Commission conducts periodic reviews of this assistance.

When considering the international context, the Authority will take into account a wide range of information. A successful solution to climate change depends on global action to reduce emissions. It is action that is paramount, not its legal form, nor where it is captured (for example, whether it appears in domestic legislation or a new international agreement). The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is an important source of information about global emissions reduction efforts, including countries’ intentions regarding 2020 action. The Authority will draw on this and other sources, including domestic legislation, policies and measures, and statements of intent, especially those made at a high political level.

This Section sets out the Authority’s proposed approach to the above three elements of international action.

Assessing global action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions

The Authority will assess the level of global climate change action to gauge how the world is tracking towards the 2 degree or lower global goal, and to compare with the Government’s existing 2020 target conditions.

There are a range of uncertainties associated with any assessment of global action. First, there are data constraints: many major emitting economies are developing countries that do not have high capabilities to measure their emissions across all sectors. Second, there are uncertainties regarding countries’ 2020 emissions reduction goals: some targets are conditional or expressed as ranges; others are not specific regarding underlying assumptions (see Tables 3a–h for a summary of 2020 goals for key major emitting countries). Finally, climate change action is not static: some countries are taking ambitious action now, others are doing less, but this will change over time both for better (countries may do more than their current pledges) and worse (countries may not implement their committed actions).

In light of these uncertainties, and to provide a comprehensive assessment of global action, the Authority will consider a broad range of indicators, including:

- progress to date – in particular, since the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Report in 1990, which recognised human-induced climate change;

- action happening now, including domestic policies and measures to track and reduce emissions (see Table 2); and

- commitments regarding future action, including domestic commitments and international undertakings under the UNFCCC (Table 3a–h).

The Authority welcomes views on the state of global action, and in particular whether and to what extent the Government’s existing 2020 target conditions have been met.

Table 2 Climate change policies and measures in key major emitters

|

Country1 |

Carbon pricing (tax, emissions trading scheme) |

Energy – Electricity supply |

Energy – Electricity demand (standards and energy efficiency measures) |

Energy – Transport |

Land-based activities, including agriculture and forests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Note: This table is indicative only and does not present a comprehensive picture of all policies and measures in place in countries at all levels of government. All information sourced from countries’ National Communications to the UNFCCC; submissions to Partnership for Market Readiness; national government websites; Globe International and International Energy Agency policies and measures database unless otherwise stated ABB, 2011 |

|||||

|

Australia |

Carbon pricing mechanism |

Renewable Energy Target |

Appliance and building standards |

Effective carbon pricing through differences in fuel tax credits for some transport |

Carbon Farming Initiative |

|

China |

Pilot emissions trading schemes in seven provinces due to begin in 2013 and 2014 |

Non-fossil fuel target |

Building energy efficiency standards |

Vehicle fuel efficiency standards |

Forest coverage target |

|

European Union |

Emissions trading scheme |

Renewable energy target |

Building energy efficiency standards |

Renewable fuel production incentives |

Soil protection |

|

India |

Coal tax |

Solar industry support |

Appliance energy efficiency standards |

Vehicle emissions standards |

Forest coverage target |

|

Indonesia |

Considering market-based mechanisms for emissions reduction in selected sectors |

Renewable energy target |

Tax exemptions for energy efficient technologies |

Vehicle emissions standards |

Significant measures to reduce forest deforestation and degradation through regulations and market-based offsets |

|

Japan |

Tax on fossil fuels |

Renewable energy target |

Energy efficiency standards and measures in residential, commercial and building sectors |

Tax incentives for purchase of lower emission intensive vehicles |

Covered under Japan’s domestic offsets scheme |

|

Republic of Korea |

Emissions trading scheme to start from 2015 |

Renewable energy target |

Appliance and building standards |

Vehicle fuel efficiency and emissions standards |

|

|

United States |

Subnational emissions trading schemes |

Subnational renewable energy targets |

Appliance and building standards |

Renewable fuel production incentives |

Support for voluntary action to reduce emissions and increase carbon sequestration |

Table 3a Australia – emissions reduction goals for key major emitters

|

Goal |

Details |

|---|---|

|

CO2-e = CO2 equivalent; GDP = gross domestic product; int. $ = international dollars; PPP = purchasing power parity; t = tonne World Resources Institute, 2012 International Monetary Fund, 2012 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012 UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011a; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011b GLOBE International, 2013 UNFCCC Dec 1/CMP.8 Clean Energy Act 2011, s 3(c)(i) |

|

|

Per cent of global emissions1 |

1.5 |

|

Per capita emissions1 |

27.5 t CO2-e |

|

GDP (int. $, PPP) per capita:2 |

$42 354 |

|

Human Development Index ranking:3 |

2 |

|

International 2020 emissions reduction goal (including conditions)4 |

Unconditional 5% reduction by 2020 on 2000 levels rising to a reduction of up to 15% or 25% in line with the conditions in Box 3. |

|

Domestic 2020 commitments and/or 2050 goals5 |

Australia’s 2020 goals are incorporated in the Clean Energy Act 2011, which also includes an objective to reduce net emissions by 80% by 2050 relative to 2000 levels.7 |

Table 3b China – emissions reduction goals for key major emitters

|

Goal |

Details |

|---|---|

|

CO2-e = CO2 equivalent; GDP = gross domestic product; int. $ = international dollars; PPP = purchasing power parity; t = tonne World Resources Institute, 2012 International Monetary Fund, 2012 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012 UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011a; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011b GLOBE International, 2013 The People’s Republic of China, 2012 |

|

|

Per cent of global emissions1 |

19.2 |

|

Per capita emissions1 |

5.6 t CO2-e |

|

GDP (int. $, PPP) per capita:2 |

$9146 |

|

Human Development Index ranking:3 |

101 |

|

International 2020 emissions reduction goal (including conditions)4 |

Lower CO2 emissions per unit of GDP by 40–45% by 2020 from the 2005 level. |

|

Domestic 2020 commitments and/or 2050 goals5 |

China’s 2020 target has been incorporated in its medium and long term economic and social development plans as a binding target. China has an interim carbon intensity target under its 12th Five Year Plan (2011–2015).6 |

Table 3c European Union (27 member states) – emissions reduction goals for key major emitters

|

Goal |

Details |

|---|---|

|

CO2-e = CO2 equivalent; GDP = gross domestic product; int. $ = international dollars; PPP = purchasing power parity; t = tonne World Resources Institute, 2011 International Monetary Fund, 2012 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012 UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011a; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011b GLOBE International, 2013 UNFCCC Dec 1/CMP.8 European Commission, 2013a |

|

|

Per cent of global emissions1 |

13.4 |

|

Per capita emissions2 |

10.3 t CO2-e |

|

GDP (int. $, PPP) per capita:3 |

$32 029 |

|

Human Development Index ranking:4 |

Ranges from 4 in the Netherlands to 57 in Bulgaria, with 17 EU27 countries in top 30. |

|

International 2020 emissions reduction goal (including conditions)5 |

Unconditional commitment to reduce emissions by 20% below 1990 levels at 2020. |

|

Domestic 2020 commitments and/or 2050 goals6 |

The EU’s 2020 target of 20% below 1990 levels is incorporated in their 2009 Climate and Energy Package. |

Table 3d India – emissions reduction goals for key major emitters

|

Goal |

Details |

|---|---|

|

CO2-e = CO2 equivalent; GDP = gross domestic product; int. $ = international dollars; PPP = purchasing power parity; t = tonne World Resources Institute, 2012 International Monetary Fund, 2012 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012 UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011a; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011b GLOBE International, 2013 Government of India, 2013 |

|

|

Per cent of global emissions1 |

4.9 |

|

Per capita emissions1 |

1.7 t CO2-e |

|

GDP (int. $, PPP) per capita:2 |

$3851 |

|

Human Development Index ranking:3 |

136 |

|

International 2020 emissions reduction goal (including conditions)4 |

Reduce emissions per unit of GDP by 20–25% by 2020 compared with 2005 levels. Emissions from the agriculture sector are excluded. |

|

Domestic 2020 commitments and/or 2050 goals5 |

In India’s Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012–2017), the Planning Commission indicates that policies should be closely monitored to ensure the achievement of the 2020 goal.6 |

Table 3e Indonesia – emissions reduction goals for key major emitters

|

Goal |

Details |

|---|---|

|

CO2-e = CO2 equivalent; GDP = gross domestic product; int. $ = international dollars; PPP = purchasing power parity; t = tonne World Resources Institute, 2012 International Monetary Fund, 2012 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012 UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011a; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011b GLOBE International, 2013 President of the Republic of Indonesia, 2011 |

|

|

Per cent of global emissions1 |

1.5 |

|

Per capita emissions1 |

2.5 t CO2-e |

|

GDP (int. $, PPP) per capita:2 |

$4958 |

|

Human Development Index ranking:3 |

121 |

|

International 2020 emissions reduction goal (including conditions)4 |

Reduce emissions by 26% by 2020 relative to business-as-usual. |

|

Domestic 2020 commitments and/or 2050 goals5 |

Indonesia’s 2011 National Action Plan for Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction contains measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in accordance with its voluntary 2020 commitment. It also states Indonesia could further reduce emissions by up to 41% by 2020 with international support.6 |

Table 3f Japan – emissions reduction goals for key major emitters

|

Goal |

Details |

|---|---|

|

CO2-e = CO2 equivalent; GDP = gross domestic product; int. $ = international dollars; PPP = purchasing power parity; t = tonne World Resources Institute, 2012 International Monetary Fund, 2012 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012 UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011a; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011b GLOBE International, 2013 |

|

|

Per cent of global emissions1 |

3.6 |

|

Per capita emissions1 |

10.6 t CO2-e |

|

GDP (int. $, PPP) per capita:2 |

$36 179 |

|

Human Development Index ranking:3 |

10 |

|

International 2020 emissions reduction goal (including conditions)4 |

25% emissions reduction by 2020 compared with 1990 levels premised on the establishment of a fair and effective international framework in which all major economies participate and on agreement by those economies on ambitious targets. |

|

Domestic 2020 commitments and/or 2050 goals5 |

The Japanese Government has a 2050 target of 80% below 1990 levels included in its Fourth Basic Environment Plan. |

Table 3g Republic of Korea – emissions reduction goals for key major emitters

|

Goal |

Details |

|---|---|

|

CO2-e = CO2 equivalent; GDP = gross domestic product; int. $ = international dollars; PPP = purchasing power parity; t = tonne World Resources Institute, 2012 International Monetary Fund, 2012 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012 UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011a; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011b GLOBE International, 2013 |

|

|

Per cent of global emissions1 |

1.5 |

|

Per capita emissions1 |

11.8 t CO2-e |

|

GDP (int. $, PPP) per capita:2 |

$32 431 |

|

Human Development Index ranking:3 |

12 |

|

International 2020 emissions reduction goal (including conditions)4 |

Reduce emissions by 30% relative to business-as-usual in 2020. |

|

Domestic 2020 commitments and/or 2050 goals5 |

The 2020 goal is included in Korea’s 2010 Framework Act on Low Carbon, Green Growth. |

Table 3h United States – emissions reduction goals for key major emitters

|

Goal |

Details |

|---|---|

|

CO2-e = CO2 equivalent; GDP = gross domestic product; int. $ = international dollars; PPP = purchasing power parity; t = tonne World Resources Institute, 2012 International Monetary Fund, 2012 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2012 UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011a; UNFCCC Secretariat, 2011b GLOBE International, 2013 United States Government, 2013 |

|

|

Per cent of global emissions1 |

18.3 |

|

Per capita emissions1 |

23.3 t CO2-e |

|

GDP (int. $, PPP) per capita:2 |

$49 802 |

|

Human Development Index ranking:3 |

3 |

|

International 2020 emissions reduction goal (including conditions)4 |

17% below 2005 levels. |

|

Domestic 2020 commitments and/or 2050 goals5 |

The US has stated it stands by its 2020 pledge, and has a 2050 goal of 83% below 2005, regardless of the passage of legislation through Congress.6 |

Comparing targets across countries

In considering an appropriate 2020 target for Australia, it is relevant to consider how the target compares with the 2020 targets and actions of other countries.

Countries have proposed 2020 targets and actions in a wide variety of forms, which means that they are difficult to compare directly. The Authority proposes comparing Australia’s target range with other countries across a range of metrics, including:

- changes in absolute emissions from a base year(s);

- changes in emissions intensity;

- deviations from business-as-usual emissions trends; and

- changes in emissions per capita.

Different metrics provide different insights. For example, changes in absolute emissions are clearly relevant, as an effective solution to climate change requires deep cuts in absolute global emissions. Emissions intensity indicates the extent to which emissions are decoupled from economic growth, an important marker of a shift to a low-emissions economy. Deviations from business-as-usual provide a direct measure of the actual emissions effect of the target. Other factors such as development levels, capability and capacity of countries are also relevant; they are discussed in Section 3.2.3.

There are a range of countries with which it might be useful to compare Australia’s mitigation goals, including other developed countries with a similar standard of living, other major emitting economies, trading partners and trade competitors. The Authority welcomes comments on which countries, and which comparative metrics, are most relevant to determining Australia’s goals.

How Australian action can influence others

The ability of Australian action to influence global action is highly relevant when considering a 2020 target for Australia. An effective solution to climate change requires action by at least all the major emitting economies, including Australia. Australia needs to consider the effects of its own actions, not only in terms of its direct impact on global emissions, but also its potential to catalyse action in other countries.

It is clear that international action affects individual country action. For example, many countries, including Australia, have linked their 2020 targets to the collective level of international action. There is also some empirical evidence to suggest that international momentum spurs domestic action: the GLOBE Climate Legislation Study notes there was a spike of domestic climate change legislation in 2009 and 2010 that may be explained by pressure from governments, civil society and international organisations relating to the 2009 UNFCCC Copenhagen Conference (GLOBE International 2013, p 19).

There remains a question whether – and to what extent – Australian action in particular influences other countries. The Authority will investigate this issue as a part of the Review, and welcomes comments on how best to understand and measure this effect.

3.2.3. Sharing global emissions budgets

Countries have very different levels of income per person, and have contributed different proportions to the past and expected future greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change. While individuals and nations disagree about their implications for action, all agree that these differences matter, as reflected in the UNFCCC (art 3). How these differences are resolved is likely to affect significantly the nature, acceptance and effectiveness of future international action.

There are many possible approaches to sharing global emissions budgets among nations. Such approaches can help countries consider their own national target and assess those of others. The Authority will consider the main underlying principles and approaches, and their implications for Australia. Views on how Australia might approach the task of determining its fair and defensible share of a global emissions budget would be welcomed.

Principles and approaches

Discussions about principles and approaches to sharing global emissions budgets begin with three questions about equity: what is being distributed, among whom and how?

The ‘what’ is either a share of the emissions reduction effort (‘effort sharing’) or a share of the remaining emissions rights (‘resource sharing’). Some take a broader view, seeing targets as part of overall national efforts on climate change, bringing technology transfer, capacity building, adaptation support and other factors into play.

The question of ‘among whom’ raises issues of trading off wellbeing across generations, and across rich and poor individuals and nations. While all approaches to sharing global emissions budgets result in a distribution between nations, several common approaches are actually based on distributing emissions among individuals, then converting this distribution to a national allocation.

The ‘how’ is interpreted as a question about the formal approach for allocating a global emissions budget.

Different parties propose different principles to take into account when allocating climate change efforts among countries. Some of the principles most commonly referred to are explained in Box 5.

Box 5 Principles to differentiate national contributions to global climate action

Capability: the greater the capacity to act, the greater the share in emissions reduction effort. A range of indicators are used, including levels of income per person, and sometimes broader notions of living standards, national economic and governance systems, and/or the potential to reduce emissions within the domestic economy.

Responsibility: the greater the contribution to emissions (generally cumulative emissions from a specified year), the greater the share of the emissions reduction effort.

Equality: all human beings have equal rights; many (not all) authors conclude this implies an equal right to emit greenhouse gases.

Access to sustainable development: emphasises that approaches to sharing mitigation should account for the global priority of meeting the interests and needs of the poorest global citizens.

Source: Climate Change Authority

These principles can be translated into different approaches for sharing global emissions budgets between nations. Different approaches embody different views on which principles are most important and how to give effect to those principles. These choices can have a significant effect on the final result. For example, approaches based on the principle of responsibility must choose the starting point for counting emissions. Counting emissions from pre-industrial times gives a very different result to counting emissions since 1990 or from the present day.

Table 4 describes some of the most common approaches for sharing mitigation action between nations, and outlines some of their advantages and disadvantages.

Table 4 Approaches to sharing global emissions budgets

|

Approach |

Description |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Source: Climate Change Authority |

|||

|

Contraction and convergence |

Emission rights per person contract over time in countries above the global average, and rise over time where they are below the global average, eventually converging to equal rights |

Simple and transparent |

Potentially impractical to expect growing developing countries to quickly converge to low per capita emissions |

|

Modified contraction and convergence |

Similar to the previous approach, but with adjustments that provide some ‘headroom’ for lower income countries whose emissions would otherwise contract immediately |

Simple and transparent |

Increased effort required by high per capita developed emitters to provide for headroom |

|

Multistage |

Staggered commitments, with countries ‘graduating’ to higher stages when they exceed predefined thresholds. For example, countries could make equal proportional reductions from their base-year emissions, with developed countries acting immediately and less wealthy nations joining over the period to 2025 |

Gradual phase-in recognises different national capacity including level of development |

Approach can be complex, requires many decisions and allows for exceptions |

|

Greenhouse development rights |

National contributions to the global mitigation task are based on capacity and responsibility. Capacity is defined as the sum of all individual income above a specified welfare threshold. Responsibility is defined as cumulative emissions since 1990, excluding emissions that correspond to consumption below the welfare threshold |

Explicitly allows for responsibility and capacity in transparent way |

Near-term targets for developed countries may be so large that approach becomes politically infeasible |

|

Equal cumulative per capita emissions |

National shares of a long term global emissions budget are assigned in equal proportion to shares of global population in a single ‘reference year’. Many of these approaches allocate national shares that account for historical emissions |

Simple and transparent |

Use of ‘reference year’ for population means that per capita emissions are not necessarily equal |

3.2.4. Economic and social implications

Australia’s budget, trajectory and targets will set the overall scale and pace of emissions reductions. Different choices will have different economic and social implications for Australia. Consideration of these impacts will help inform what Australia should do over time.

The Authority will consider the broad implications of the minimum 5 per cent emissions reduction target for the Australian economy. From this starting point, the economic and social impacts of more stringent targets can be assessed. To the extent possible, the Authority will endeavour to examine how these impacts might vary across different regions and sectors.

The Review is not focused on the economic and social implications of carbon pricing per se, nor on the implications of global action to address climate change. Rather, the purpose of considering these issues is to indicate how economic and social impacts are likely to change as Australia’s goals become more ambitious.

The determinants of the relative impacts of different targets include:

- Australia’s emissions reduction opportunities (which are likely to change over time);

- the broader policy mix aimed at reducing emissions;

- the impact of international linking;

- the level of the carbon price; and

- the impact of other countries’ actions.

Australia’s emissions reduction opportunities

The emissions reduction opportunities available in Australia and how they change over time will be a key determinant of the economic and social impacts of any given target and trajectory. Opportunities include low-emissions technologies, energy efficiency improvements, changing production processes and materials, and shifting consumer preferences.

Through economic modelling and analysis, the Review will consider Australia’s emissions reduction opportunities – their scale and costs, and the sectors and regions in which they might be available. This will include sensitivity analysis of key areas of uncertainty. The Authority welcomes comments and analysis on these matters.

The policy mix

The economic and social impacts associated with any particular target will, in part, depend on the suite of policies in place to achieve them. Some policies will reduce emissions more cost-effectively than others.

While the carbon pricing mechanism has been designed as the central policy measure to achieve Australia’s emissions reduction targets, a number of other policies also drive emissions reductions. These include the Renewable Energy Target, which reduces emissions from sources also covered by the carbon pricing mechanism, and state-based controls on land clearing, which reduce emissions from sources that are not covered.

In assessing the economic and social impacts of different goals, the Review will take account of the full suite of policies contributing to emissions reductions.

International trade in emissions units

The carbon pricing mechanism has been designed to link to international carbon markets from 1 July 2015. The objective here is to enable Australia’s targets and caps to be met through a cost-effective mix of domestic and international emissions reductions. These arrangements have important implications for assessing the economic and social implications of different targets, given the impact linkages could have on the carbon price Australian emitters face.

In a closed system with no links, a more ambitious target and caps would lead to a higher carbon price. This is because the carbon price is a function of supply (the number of permits available under the cap) and demand (emissions from covered sources). With supply restricted due to more stringent caps, the price would rise.

With international linking, liable entities can choose to meet some of their liability through the purchase of international units. Liable entities have a clear incentive to source emissions units at the lowest cost. If the price of an international unit is cheaper than a domestic unit or than reducing emissions in Australia, they would purchase an international unit.

Previous analysis suggests Australia’s domestic price is likely to converge to the international price (Commonwealth of Australia, 2011). Australia’s carbon market is relatively small compared with the international market. The EU ETS is estimated to cover nearly six times the amount of emissions as the Australian carbon pricing mechanism in 2013 (Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, 2012b; European Commission, 2013b). Setting more ambitious emissions reduction goals will reduce the supply of domestic units, but have only a relatively small impact on aggregate demand for international units in the much larger global market.

This means Australia’s choice of target and caps may not have a significant impact on the carbon price and, in turn, have only a limited impact on the level of Australia’s domestic emissions. Instead, Australia’s domestic emissions could depend primarily on the international carbon price. In this case, Australia’s choice of target and caps would change the volume of international units purchased. More stringent caps would reduce the number of domestic units available and increase the use of international units. The level of the target and caps will also affect government revenues: more stringent caps leave fewer units to auction, generating less auction revenue.

Australia’s choice of target and caps may directly affect the carbon price and the level of domestic emissions. For example:

While Australia comprises a relatively small share of the global market, it may still have a material impact on demand for international units, and its choice of target and caps may shift market expectations. More stringent caps would lead to a higher international carbon price, driving greater domestic emissions reductions.

If the target and caps are set at a level that makes the limit on international units become binding, the Australian price would need to rise above the international price to drive greater domestic emissions reductions. The carbon pricing mechanism has generous allowances for international units: liable parties can use them to meet up to 50 per cent of their obligation.

Due to the importance of international trade in emissions units, the Review will investigate the outlook for the international carbon market, the implications for availability and price of international units in Australia, and the likelihood and consequences of the limit on imports becoming binding. The Authority welcomes views and analysis on these issues.

The level of the carbon price and impact of actions by other countries

The carbon price will be a key determinant of the relative economic and social implications of different targets. The level of the carbon price during the next 10, 20 and 40 years is very uncertain, so the Review will assess the relative impacts of moving from the minimum 5 per cent emissions reduction target to a more ambitious target for a range of possible carbon prices.

The future carbon price will largely be a function of the emissions reduction goals of other countries. Therefore, the Review will assess different carbon price scenarios using economic modelling of different international goals.

The actions taken by other countries to reduce emissions will have an impact on the Australian economy, irrespective of Australia’s action. For example, action on climate change in key trading partners is likely to have an impact on the demand for Australia’s goods and services, and also change the cost of goods and services that Australia imports. The economic modelling of different levels of international action will shed light on these trade impacts, although they are not the primary focus of the Review.